Team Fur News - Dec23

Team Fur News - Dec23

Rooster!

By FUR-FISH-GAME Editor, John D. Taylor

English setters Harry and his sister Ellen with a brace of Nebraska roosters.

It all began back in the early 1970s, in October, with a lights-flashing, sirens-roaring fire truck racing down Blymire Road, part of which was still gravel and laden with potholes.

My family lived on the paved part of Blymire Road, in a small but growing housing development, perched on the hill above the Dallastown Area High School.

My father, curious about where the fire was, chased after that fire truck, jogging past Lion’s Park, the leaves just beginning to turn, then down over the hill, to where the road turned into gravel. Before the fire truck turned into one of the new houses being built there, he stepped into a pothole and heard something snap down in his leg.

While the fire was a false alarm, the pain rising in his leg wasn’t. He had a hairline fracture in his tibia. He limped home. Later, a doctor put a cast on his leg, sentencing him to eight weeks in plaster of Paris.

Naturally, we were all worried about Dad. And while this sounds kind of childish to me now, to a 13-year-old kid ravenous about hunting and trapping, I saw Dad's injury as a serious hit to my outdoor adventures.

Pheasant season was coming. For York County male teenyboppers, pheasant hunting was a rite of passage. Two rooster tails sticking out the back of your game bag meant you were SOMETHING in the eyes of the society of young hunters. And that’s why it seemed like my father’s interest in fire engines would delay my chances of achieving that milestone.

Long days passed – in kid time they were centuries, eons – waiting for some sort of verdict on how I’d participate in the pheasant opener without my father. Game laws prevented me from hunting alone at that age.

Then came the phone call.

My uncle, Dave Reichard, said I could join him for a morning pheasant hunt on the edges of Red Lion.

The bluebird of happiness lifted me to Cloud Nine.

That morning, I donned my recently-deceased grandfather’s canvas hunting coat, vinyl-fronted canvas hunting pants (to shuck briars and multiflora rose), a green felt slouch hat, and rode in Uncle Dave's pickup truck to his hunting spot, a cornfield, some of it harvested, some not, quite near his parent’s home outside of town. We were joined by his younger brother, Steve – he loved to tell whopper stories about his many hunting exploits to anyone who would listen, especially a wide-eyed kid like me – and a couple of Steve’s friends.

Back then, Pennsylvania pheasant hunters shot more than 1 million roosters annually. Many of these birds were the natural product of wooly, uncropped corners of farm country and cornfields infested with foxtail and other “weeds” in the days before glyphosate. Some were also raised and released by sportsmen’s clubs, and a modest stocking program from the Pennsylvania Game Commission added to the pot. To put this in perspective, 1 million-plus roosters is a reasonable year’s pheasant bag in South Dakota nowadays.

Better, southcentral Pennsylvania was the epicenter of this – especially York, Adams and Lancaster counties. People came from all over the East to hunt pheasants in our area. Tiny cinder-block-built Collinsville Discount Center, a rural general store that typically catered to southern York County farmers – the “Southern Mall,” Uncle Dave jokingly called it – was always packed the Friday night before the pheasant opener with hunters buying shells, guns, canvas hunting clothes and other gear.

We didn’t use dogs to hunt pheasants then, (although some hunters preferred beagles). No, sir, we put on drives, flushing the birds from the foxtail-covered cornfields.

Anyhow, after an unproductive drive or two in the hunt that morning, the adults told me to post on a field road in the middle of the cornfield, saying they would flush birds towards me.

“Now Johnny,” Steve hollered, laughing, as the men began pushing through the corn, “We’re coming through, so don’t you shoot down on the ground at us.”

I’d passed the Dallastown Middle School-run Game Commission Hunter’s Safety program with higher grades than probably any other class I'd attended, and had no intention of doing this, but I assured him I wouldn’t.

A breeze rattled the cornstalk leaves and the crunch of distant footsteps, brown canvas scraping the stalks, grew closer. A rooster pheasant jumped, squawking, and one of the men in the drive brought it down with a hump-backed 12 gauge Browning autoloader, just like Uncle Dave and Steve had.

More birds flushed, including some hens, and the drivers collected more roosters.

Then it happened.

About 25 yards down a corn row, a running rooster spotted me and took wing, flying right above my head, maybe 15 yards high.

I raised my Black Bart .410 H&R single shot – it had a chromed action, black lacquer stock and fore-end, and I’d convinced my father I should have it instead of a 12 or 20 gauge because I’d foolishly believed the other boys’ tales of getting kicked on their rumps by shooting a big 12 – pointed it at the escaping rooster, cocked the hammer and let fly…

BANG!

Nothing happened, the bird just sailed on.

When I opened the action, a smoking .410 hull thunked out and sailed behind me into the dense foxtail understory.

I quickly pulled another long red shotshell from the loops in Grandpa’s game-coat pocket, shoved it into the shotgun’s breech and waited.

Another brightly colored cock pheasant sailed over. I shot, same results.

Then another, and another. Again, no birds falling.

I started cussing, loudly, wondering if my hunting group knew a kid could spray blue oaths quite like that, or if they were laughing at me.

In total, seven gaudy roosters flew over me that morning and I missed every single one. I got ribbed from the men and although it didn’t feel too good, I knew it was just for fun.

But something else happened that day.

I became a lifelong bird hunter.

It started because pheasants offered me a challenge. I could shoot a pile of squirrels with that .410 but didn’t know how to be a wingshooter. And I sorely wanted to be one, to earn the esteem of men like Uncle Dave, Steve, and his friends.

A season passed. Black Bart was traded in on a 20-gauge Winchester Model 1300 pump gun that didn’t kick at all. (Those guys were full of it.)

One Saturday, my father and I were hunting on a northern York County State Game Lands, pushing a weedy powerline, hoping to bump up pheasants. Dad really didn’t like to hunt, particularly small game, because he’d had a bad experience with a landowner after a rooster fell on the wrong side the guy’s fence.

Until I grew ravenous about bird hunting, my Dad never picked up the Lefever Nitro Special side-by-side 12 gauge that had been his father’s and was now his.

I was serving as the bird dog that day, kicking into anything a pheasant could hide. A couple hundred yards along that powerline, from a patch of flaming sumac trees, a rooster rose cackling.

I swung the Winchester on it, pulled the trigger and it fell – my first pheasant on the wing. And that pretty much clinched it. I’d be a bird hunter.

At 16, I could drive and hunt alone, which saved my blessed father unwanted trips to the hinterlands to chase roosters. While in college, I developed a solo pheasant hunting system that involved meandering routes through fields, walking fast then stopping and holding for a few moments to unnerve birds and flush them. I occasionally hunted with friends and family, but mostly I hunted alone because my schedule and the rest of the world’s never seemed to jive.

During the early 1980s, a German shorthair named Briarcliff Arcturus, after the star, came into my life. I called him Jack, and he was my best buddy.

Jack expanded my bird-hunting horizons. We made our first bird-hunting junket, for pheasants and quail, to southwestern Kansas in the middle 1980s. Together, we discovered ruffed grouse in the mountains near home, too. This coincided with plummeting pheasant numbers in the late 1980s and 1990s. We found enough public land pheasants, most of them now stocked not wild, to keep us happy, but the quality of the hunt was slipping away almost as fast as housing developments, shopping malls, and industrial parks gobbled up habitat.

By the late 1990s, those million pheasant bags of the 1970s were reduced to 250,000 birds, most of them stocked. To lose such abundance sparked a conservation anger in me.

Ruffed grouse soon dominated my bird hunting. They were wild, unstockable. And in Penn’s Woods the habitat problem wasn’t likely to be an issue.

In the late 1980s, my first English setter, Nash, joined Jack and I. We traveled to Minnesota to hunt the gray phase grouse of the Great Northwoods.

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that pheasants began a slow, steady return to my bird hunting.

Falling in love with prairie started it. In a reverse of what happened back East, prairie’s grouse, sharptails and prairie chickens, captivated me. The occasional pheasants found with them, big wild birds, reminded me of a love I’d left behind.

English setters Evan and Shana helped me remember what fun pheasants were. Evan’s bold slashes through CRP grasslands were a joy to behold. He literally set shots for me on pheasants. Somehow, he positioned the rooster, me and himself for a stunning point, creating the opportunity for the shot. I’ve never seen another dog do that quite as well. He mastered it.

Harry, his mother Beryl, and sister Ellen came along in the 2010s, all good sharptail dogs and efficient pheasant hunters. But pheasants were really Harry’s birds. Busting through frozen cattails in the middle of winter to pin roosters on the edge of a slough was Harry’s gig.

Now, year-and-a-half old Willa stands on the shoulders of these giants, learning that pheasants, and prairie grouse, are her birds, too.

Finding pheasant hunting all those years ago was such a blessing. Yet I still wonder what possessed my father to chase after that fire engine.

Outdoors Contributes $395 Billion to US Economy

The 2022 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, released recently by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), says some $395 billion was contributed to the U.S. economy via the outdoors. Breaking this down, hunting and fishing contributed $145 billion, wildlife watching $250 billion. According to the report, 39 million people (15% of the U.S. population 16 years and older) participated in recreational fishing, 14 million people (5.5% of the U.S. population 16 years and older) participated in hunting, more than 148 million watched wildlife, more than 47 million participated in target shooting, and more than 19 million participated in archery. The National Survey is conducted every five years as a gauge of participation in the outdoors. “Outdoor recreation is one of our nation’s largest economic engines. It touches all American’s, from small rural towns to those living in bustling cities and continues to be a powerful force in our nation’s economy,” said Chuck Sykes, Director of the Alabama Division of Wildlife & Freshwater Fisheries and President of the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. The survey is a partnership between the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, USFWS and the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago, a highly respected research and survey company. The report is available at https://digitalmedia.fws.gov/digital/collection/document/id/2321/rec/1

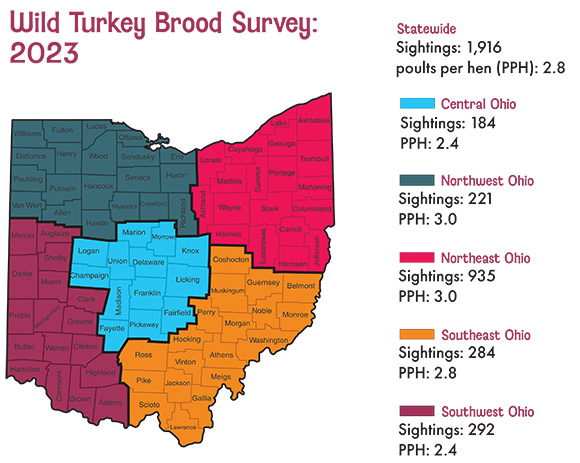

Ohio’s Turkey Hatch Up

Ohio’s turkey poult index was up for the third year in a row. Photo: NWTF

Ohio's wild turkey poult index, a metric used to estimate nest success, was above average for the third year in a row, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) Division of Wildlife. The 2023 Ohio index was 2.8 poults per hen, above the 10-year average of 2.7 poults per hen. ODNR relies on public reports of wild turkeys and their poults, logged in July and August, to estimate nest success. The index can serve as an indicator of wild turkey population trends and inform harvest regulations in future years. Turkey brood success is largely influenced by weather conditions, habitat, and predation. The 2021 and 2022 brood surveys also showed above average nest productivity, benefitting turkey populations after several years of below average results. The statewide average poults per hen in 2022 was 3.0, and 3.1 in 2021. This year, turkey poult production varied slightly by region. In northeast and northwest Ohio, the index was 3.0 poults per hen. It was 2.8 in southeast Ohio, and 2.4 poults per hen in central and southwest Ohio. Because of habitat availability, Ohio’s turkey populations are typically strongest in the eastern and southern counties.

Map of Ohio results. (Click image to view larger version)

Extinctions and Protections, South and North

Bachman’s warbler is one of 21 species declared extinct by the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Art: Louis Agassiz Fuertes

This fall, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) finalized a rule removing 21 species from the Endangered Species Act because the agency determined these species were extinct. Many of the species, including several varieties of freshwater mussels and Bachman’s warbler, were wildlife of the South. “This should be a wake-up call to the reality of our extinction crisis, and human activity’s role threatening species,” said Southern Environmental Law Center’s Wildlife Program Leader, Ramona McGee. “The stakes are higher for wildlife here in the South. We host a globally significant variety of plants and animals that are under mounting pressure because of humanmade threats, including climate change and habitat loss.” Unfortunately, she continued, some species received ESA protections when they were already perilously close or suspected to be extinct. Despite this, she said, the ESA remains one of the most effective and comprehensive conservation laws in the world. She also lauded the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act – it supports state and tribal wildlife agencies’ work conserving species before they risk extinction. Meanwhile, in Maine eight new species were added to the state’s Endangered and Threatened Species list. This included five birds, one bat, a bee and a beetle. Two of these species, the saltmarsh sparrow and Ashton’s cuckoo bumble bee, are listed as endangered, and the other six as threatened. Four of the additions are threatened by climate change: The saltmarsh sparrow breeds in coastal saltmarshes of south-central Maine where nests are vulnerable to flooding during high tides associated with sea level rise. Similarly, the margined tiger beetle relies on a small number of saltmarsh-sand dune areas that are threatened by rising seas and associated storm surge. Likewise, Bicknell’s thrush and the blackpoll warbler occupy high-elevation spruce-fir forests of central and western Maine, habitats that are predicted to retract to higher elevations, or disappear altogether. There are now 57 species listed as state threatened or endangered in Maine. The Maine Endangered and Threatened Species Listing Handbook (a PDF document) can provide complete information about these species. Visit https://www.maine.gov/ifw/fish-wildlife/wildlife/endangered-threatened-species/

UC Davis to Safeguard Spring-run Chinook Salmon Broodstock

Due to a “cohort collapse” – so few spring run Chinook salmon have returned from the

ocean to breed in streams – conservationists are capturing juvenile fish to start a

hatchery program and protect Chinook genetics. Photo: CDFW

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) fisheries biologists are pursuing urgent measures this fall to save some of the last remaining Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon after the numbers returning from the ocean this year fell sharply toward extinction. Biologists call this year’s sharp decline a “cohort collapse,” because so few threatened adult spring-run Chinook salmon returned to the small streams still accessible to them. Mill and Deer Creek — two of three streams that hold the remaining independent spring-run populations — each saw fewer than 25 returning adults. Returns to Butte Creek, a third independent population, were the lowest since 1991 and adults further suffered impacts of a canal failure in the watershed. “We are running out of options,” said Cathy Marcinkevage, assistant regional administrator for NOAA Fisheries West Coast region. “We want this species to thrive in the wild, but right now we are worried about losing them.” Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon typically follow a three- to four-year life cycle, a strategy that usually provides some resilience to catastrophic events occurring to an individual year class. While other year-classes (or cohorts) will return in coming years, the 2019-2022 drought impacted multiple cohorts, increasing risks for extirpation. Biologists intend to capture juvenile fish from Mill, Deer and Butte creeks to start a conservation hatchery program that will safeguard the genetic heritage of the species. UC Davis will house the captive broodstock at the University’s Center for Aquatic Biology and Aquaculture (CABA) for the next two years until a longer-term facility is identified. “These drastically low returns come at a time when we’ve already been taking extreme measures to protect salmon strongholds and eliminate existing barriers keeping them from their historic habitat,” said CDFW Director Charlton H. Bonham. “We’ve got to continue to do everything we can to preserve these iconic fish.” Conservation hatcheries are vital to the protection and recovery of other highly imperiled salmon stocks, including endangered Sacramento River winter-run Chinook and Central California Coast Coho salmon. The remaining populations of spring-run Chinook are declining more than 10% each year and face high risk of extinction, according to an updated viability analysis by NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

WI DNR confirms CWD in Trempealeau and Polk Counties

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has confirmed CWD in wild deer in

Trempealeau and Polk counties. Photo:Anthony Roberts/Unsplash

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has confirmed wild deer in Trempealeau and Polk counties have tested positive for chronic wasting disease (CWD). The Trempealeau deer was a hunter-harvested 3-year-old doe taken in Hale. It’s the first confirmed CWD-positive wild deer detected in Trempealeau County. The Polk County deer was a hunter-harvested 3-year-old doe from Apple River. The deer was and is the first confirmed wild deer CWD-positive detected in Polk County. As a result of the Trempealeau discovery, Trempealeau and Jackson counties will renew the baiting and feeding bans already in place. Eau Claire County currently has a baiting and feeding ban in place from positive detections there, so the ban in Eau Claire is not renewed by this detection because it’s longer than the two-year ban that would result from this detection. As a result of the Polk detection, the county will begin a three-year baiting and feeding ban on December 1. Barron County will renew that ban, already in place. State law requires that the DNR enact a three-year baiting and feeding ban in counties where CWD has been detected, as well as a two-year ban in adjoining counties within 10 miles of a CWD detection. If additional CWD cases are found during the lifetime of a ban, the ban will renew for an additional two or three years. DNR reminds the public that it is illegal to hunt over an area previously used for legal baiting and feeding until that area is completely free of bait or feed for 10 consecutive days. Baiting or feeding deer encourages them to congregate unnaturally around a shared food source where infected deer can spread CWD through direct contact with healthy deer or by leaving behind infectious prions in their saliva, blood, feces and urine. DNR is asking deer hunters in these counties to help with efforts to identify where CWD occurs on the landscape by having their deer tested for the disease. Also, hunters are encouraged to properly dispose of deer carcass waste by locating a designated dumpster, transfer station or landfill location. This helps slow the spread of CWD. More information about CWD can be found on the DNR’s CWD webpage. Visit https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/wildlifehabitat/cwd

California Free Hunting Days

California is offering two free hunting days for residents who want to

experience the sport. Photo: CDFW photo

It’s the thrill of seeing a high-octane pointing dog slam to a standstill, or having a front-row seat as a wetland comes to life at dawn, the chaos of a valley quail covey erupting from cover, the heart-pounding excitement of a turkey’s gobble. It’s also a chance to share a wild game meal with friends and family they can’t get in any grocery store, farmer’s market or five-star restaurant. Californians will have two opportunities to acquaint themselves with the hunting experience during California’s Free Hunting Days, being held this year on Nov. 25, 2023, and April 13, 2024. On these days, eligible California residents may hunt without purchasing a California hunting license, provided they can provide proof of completion of a hunter education course, possession of a valid Free Hunt Days Registration, and any required tags, federal entitlements and entry permits. Participants must also be accompanied by a mentor at least 21 years old, who holds a valid California hunting license. “The dates were chosen carefully and intentionally to provide the widest variety of hunting opportunities and options for anyone interested in giving hunting a try,” said Taylor Williams, California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) Recruit, Retain, Reactivate Manager. “We encourage California residents to try Free Hunting Days and discover their own connection to nature and wild food in our state.” For more information, visit https://wildlife.ca.gov/Licensing/Hunting/Free-Hunting-Days

More invasive crayfish

A signal crayfish. Photo: MDNR

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) has confirmed the presence of signal crayfish, an invasive non-native species, in Lake Winona, adjacent to Alexandria in Douglas County. This is the first confirmation of signal crayfish in Minnesota waters. Signal crayfish are larger and more aggressive than native Minnesota crayfish. They eat aquatic plants, detritus, fish eggs, smaller crayfish species and other beneficial native invertebrates and can outcompete native species for food and habitat. Signal crayfish can spread between connected waterways or be transported by people. They can also crawl over land at night and during wet weather. Signal crayfish are bluish brown to reddish-brown in color, with large, smooth claws and a smooth carapace – the protective covering over their head and mid-section. They have a white or pale blue-green patch near their claw hinge, which looks like a signal flag. A commercial harvester contacted DNR after trapping two signal crayfish in Lake Winona. Since then, the harvester has found eight additional signal crayfish in Lake Winona. One female was among the 10 adult signal crayfish captured and removed from Lake Winona. DNR followed up with trapping in Lake Winona and in two adjacent connected lakes but did not capture additional signal crayfish. Currently, there’s no evidence of reproduction in the lake. “Importing live, non-native crayfish to Minnesota is illegal without a permit,” DNR Aquatic Invertebrate Biologist Don Eaton said. “Regardless of species, it is illegal to release non-native plants or animals into the environment. We deeply appreciate that people harvesting crayfish are keeping a close watch on their catch and that, in this case, the harvester quickly reported this unusual-looking crayfish to the DNR.” DNR is asking the public to report any possible invasive crayfish sightings. The sighting should include the exact location and photos. Keep the specimen, and submit the observations to EDDMapS (eddmaps.org/project/midwest/tools/infestedwaters/?page=map) or their local invasive species specialist (mndnr.gov/invasives/ais/contacts.html).

New NC Record Channel Catfish

Justin Hall, of Reidsville, North Carolina, and his 27-pound 7-ounce channel cat record fish.

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission has certified a new channel catfish state record. On May 21, 2023, Justin Hall, of Reidsville, reeled in a 27-pound 7-ounce channel cat, from a local farm pond near his home in Rockingham County. Hall’s fish broke the previous record of 26 pounds caught in the Neuse River in 2021. Hall has been fishing this pond for years, but rarely caught channel catfish from it -- until May, when his 13-year-old son caught what he estimated to have been a 25-plus pounder. They returned it to the water, unaware of the record held at that time. “I told a friend about my son’s catch,” Hall said, “and he told me it might have been big enough to beat the state record.” A week later, using bread dough as bait and his Big Cat Fever Casting Rod and Zebco Big Cat XT reel, he caught the record-breaker. His wife went down to the waterline to bring the fish in a net, and it bent the net, he noted. The fish measured 36-1/4 inches long and 24-7/8 inches in girth. To qualify for a state freshwater fish record, anglers must catch the fish by rod and reel or cane pole. The fish must be weighed on a scale certified by the state Department of Agriculture and witnessed by at least one observer. It must be identified by a fisheries biologist from the Commission and the angler must submit an application with a full, side-view photo of the fish. For a list of all freshwater fish state records in North Carolina or more information on the State Record Fish Program, visit the State Record Fish program webpage, https://www.ncwildlife.org/Fishing/Fishing-Records/NC-Freshwater-Fishing-State-Record-Program

Upcoming Events

New York Fur Auction

The Fulton-Montgomery Fur Harvesters and the Foothills Trappers Association will host two fur 2024 auctions in Herkimer, New York, at the Herkimer VFW post. The auctions will be held February 4 and April 13. Doors open at 6 a.m., fur sales begin at 8 a.m. For more information, contact Paul Johnson, president of Fulton-Montgomery Trappers at (315) 429-2969 or Neil Sowle, treasurer of Foothills Trappers at (518) 883-5467.

West Virginia Trappers Fur Auction

The West Virginia Trappers Association will hold their annual Fur Auction March 1-3, 2024, at the Gilmer County Recreation Center, 1365 Sycamore Run Road, Glenville, West Virginia. Vendors will be present throughout the weekend. Consignment for finished fur, etc., begins at 9 a.m., Friday, March 1, and continues through Saturday, March 2. The fur auction will be held Sunday, March 3, at 1 p.m. A board of directors meeting will held be Friday, March 1, at 7p.m. Admission is free, and all are welcome to attend. For more information, contact Jeremiah Whitlatch, at (304) 916-3329 visit www.wvtrappers.com

Order Early for Christmas Delivery

Your annual reminder that FUR-FISH-GAME Magazine is very much not Amazon. We are still family owned, and when you order products from us it's just a couple of folks here in the office filling those orders. As such, if you're hoping to get merchandise delvered in time for Christmas, please get your order in by December 8. Anything after that and there are no guarantees. Thank you for your understanding. You can order products on our website here: FUR-FISH-GAME Products.

What’s Coming in January

Make The Call - Alan Davy shares how to use deer calls and rattling to summon the buck of your dreams. It’s never too late to try calling to lure deer into range.

Thermals And How To Use Them - Understanding these air currents can put a hunter a lot closer to tagging big game, especially elk, as Josh Honeycutt explains.

Pennsylvania Fisher Trapping - Tom Edgington shares how three Pennsylvania trappers, Family members, tried fisher trapping and found success using dirt hole sets.

The Unvarnished Truth About Ice Fishing with Kids - Phil Goes’s honest and humorous look at ice fishing with kids, will leave a smile on your face as he discusses some of the problems and joys of ice fishing with children.

Innovative Cats - “I’m of the opinion that bobcat trappers tend to be among the most creative, the most innovative,” writes Tom Miranda in this look at what works for catching bobcats.

Other stories include:

• Crow Hunting - Kevin Dunse explores an off-season wingshooting adventure, hunting crows. Can you eat crow? Dunse says you can, and they’re pretty tasty.

• The Low Hunters - William Carter, a 14-year-old, tells how he and his brother are “low” hunters, who, despite not putting a lot of effort into their outdoor adventures, still come up with game and tales to share about it.

• Texas Late-Season Deer Road Trip -- Luke Clayton offers suggestions on how deer hunters can gather their venison while enjoying Texas’s famed whitetail hunting late into deer season. He also includes ideas on how to incorporate an exotic game or feral hog hunt into this mix as well.

• Modifying Trap Stabilizers - Kevin Waterman shares his solutions for using stabilizers for bodygrip traps in rocky waterways and other uses.

• Decoying Deer - Judd Cooney tells how using deer decoys, often the bane of some hunters, can produce some outstanding results and wild stories.

• Fox In The Box – Catching foxes in box traps? John Murray tells you how and proves this can be a viable alternative for some situations.

• To Build A Muzzleloader - Robert E. Sellers shares how building a muzzleloader from spare parts he had around his shop brought him healing as he recovered from surgery.

• Uncle Sam’s Sling - David Darlington offers tips on how a military-style sling can be used to steady rifle shots.

• Trapping With “Peengie” - Phil Goes shares his adventure with “Peengie” his young son’s humorous alter ego.

End of the Line Photo of the Month

Jeremiah Gracie (and Trapper), Lincoln, VT

SUBSCRIBE TO FUR-FISH-GAME Magazine