Guns & Ammo: Specialty Loads Varmint/Deer

Guns & Ammo: Specialty Loads Varmint/Deer

By Gun Rack Editor Ed Hall

There is a growing if still small trend among savvy hunters to take up .243 and .25-06 rifles for antelope and deer, instead of the more traditional .270 or .30 cartridges. Better bullets and loads are making the smaller bores more than adequate.

It is also pretty common for a savvy predator pro to leave the .223 or .22-250 at home on a windy day, in favor of a .243. Again, specialty bullets and tailored loads are making this not only possible but practical. And where these trends converge, we may find the emergence of the long-sought all-round rifle for deer and varmints.

But first, a little gun history. The .243 came on like gang busters when it was introduced by Winchester in 1955. It delivered high velocity with minimal recoil and put deer on the ground—when the bullet worked right. But stories of bullet failure proliferated, suggesting that the smaller-diameter pill just could not be properly made to provide a good mushroom and also hold together for penetration. That was more than a half-century ago, and much has changed in bullet design since. Yet a great many deer hunters are still wary of the .243’s early bad reputation.

Maybe it’s time they got with the times. Hunting bullets in general have been getting better and better. Bonding the lead core to the jacket was an immense improvement for big game. A patent once limited the availability of such bullets. Guess the patent ran out, because everybody’s doing it these days.

Randy and Connie Brooks bought the old Barnes bullet company in 1974 and brought their all-copper “X” bullet to market way back in 1989. Hornady and Nosler now offer similar products (as close as they can come without infringing Barnes’ still-enforced patents). These monolithic bullets are well-nigh unfailing, and when used in the .243, make the cartridge relatively unfailing for deer and antelope, too.

In the varmint realm, the .243 also more than holds its own, outshooting even the “gold standard” .22-250 on a windy day. Predator hunters in the wide-open West long ago noted the better wind-bucking performance of the .243.

So, why not use the same rifle all of the time for both deer and coyote?

An old adage says, “The smaller the bullet, the smaller the case, the smaller the group.” While this is pretty much true in benchrest rifles, the difference is negligible if not undetectable in over-the-counter rifles. And, somewhat surprisingly, the most popular benchrest cartridge these days is actually .243 diameter, the 6mm PPC, using an efficiently shaped, smaller case based on the .220 Russian case, loaded about 600 ft/s slower than the .243 Winchester.

Most of today’s bolt rifles deliver close to MOA accuracy, and it just doesn’t matter whether they are chambered for .223, .22-250 or .243. My new Savage lightweight .243 hovers in the realm 1/2 MOA.

The .243 is right at home with 55- and 60-grain bullets, the same as are popular in .22-250. They are just about identical in ballistic coefficient, too, right around .250, and the larger bore of the .243 provides a faster initial push.

Hornady says their .22-250 load with a 55-grain bullet has a muzzle velocity of 3,680 ft/s. Their .243 load drives a 58-grain bullet at 3,750, and their new Superformance .243 load drives the same 58-grain bullet to 3,925.

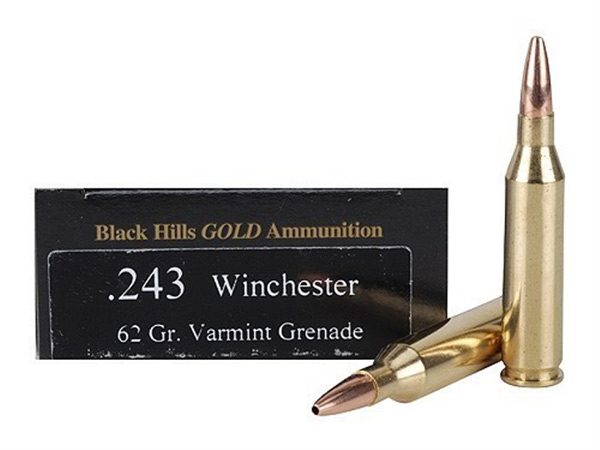

Black Hills offers a load in .243 that uses the pelt-saving Barnes Varmint Grenade bullet, which virtually vaporizes on impact, leaving no exit hole in a coyote pelt. Nosler’s website lists their Varmageddon ammo in .243 using a 55-grain bullet, either hollow point or Ballistic Tip. Remington, Winchester, and Federal also offer .243 ammo with thinly jacketed, explosive varmint bullets. Black Hills and Hornady offer the 58-grain Hornady V-Max bullet.

Of course, there are plenty of traditional-style heavier bullets for big game mostly in the common 95 to 100 grains. For the latest and greatest in premium game bullets, look to Remington loads using 95-grain Swift Sirocco UltraBonded, a 100-grain Core-Lokt Ultra Bonded, and an 80-grain monolithic Copper Solid. Winchester offers 100-grain Power Max Bonded and a 90-grain Power Core 95/5. Hornady offers their 80-grain GMX monolithic. Federal offers the 85-grain Trophy Copper, which is a Barnes TSX, and the traditional 100-grain Nosler Partition. Black Hills offers a load using the Hornady 80-grain GMX and one using an 85-grain Barnes TSX. Nosler Trophy Grade ammunition offers an 85-grain Partition and their 90-grain E-Tip monolithic. Barnes Vor-TX ammunition includes .243 using their 80-grain TTSX.

No doubt there are plenty of top choices for medium big-game with a .243.

The still relatively new .243 WSSM (less than 10 years on the market) is one of the hottest predator rounds ever. This ultra-short cartridge takes the short-magnum design to the extreme. The fat, sharp-shouldered powder room contributes to efficient powder burn, and more capacity increases muzzle velocities 100 to 200 ft/s over a standard .243, taking it into the realm of the .240 Weatherby Magnum, which, by the way, is a superior predator round if you don’t mind paying $3 a shot (or handload it, as I do).

Equally popular for deer and antelope is the .25-06. In fact, it is often called the best antelope cartridge. It rarely gets a glance as a predator round. Perhaps it’s time for that to change, too.

Looking at Winchester’s 2011 rifle ammunition tables, we may easily compare it to the .22-250 using similar varmint bullets. A .22-250 with Winchester’s 55-grain Ballistic Silvertip (by Nosler) and a .25-06 using Winchester’s 85-grain Ballistic Silvertip have virtually identical ballistic paths out to 500 yards, where the .25-06 actually wins by a half-inch, 32.5 inches of drop against 33 inches for the .22-250.

I checked Sierra’s ballistics program to get wind deflection figures and found that the 85-grain Ballistic Silvertip in .25-06 beats the .22-250 with 22 inches of drift versus 27 for the .22-250. If you really want a great wind bullet for long-range antelope, switch to Winchester’s .25-06 load using the 110-grain Accubond.

At 500 yards, drift in a 10-mph crosswind will be just 19 inches and change.

I always have considered wind drift a bigger challenge than bullet drop, and nailing bullet drop these days is even easier with a laser rangefinder. Take the reading and consult a drop table taped to the scope. But wind drift is as difficult to handle as ever. There just isn’t any way to accurately gauge the vagaries of wind speed and direction between the rifle muzzle and a distant target.

A varmint-barreled, left-hand Savage model 110 in .25-06 has long been one of my favorite rifles. It is currently topped with a Burris 6-24X and loaded with 75-grain Hornady V-Max bullets at 3,700 ft/s for woodchucks and the occasional coyote. I step up to Nosler 100-grain Ballistic Tips at 3,300 ft/s for long-range woodchucks on a windy day. And that 100-grain woodchuck load is also one of my deer loads. Shooting woodchucks at 300 yards all summer long, with the actual deer load, is the best practice one can get.

If I lived out West in prairie dog country, I’m not sure I would want to take the punishment from three or four boxes of .25-06 in an afternoon. But here in the Northeast, for me, anyway, that kind of volume shooting is not an issue.

Big brother to the .243 WSSM is the .25 WSSM, which exactly duplicates velocities of the .25-06, and while the .25-06 has a much greater variety of available ammunition, the .25 WSSM fits a really short action.

There is factory ammunition aplenty for just about every modern big-game rifle, but if you want to turn a pet .257 Roberts into a predator rifle, you must handload. The extra powder capacity of the case gives the .25-06 a 200 to 250 ft/s boost over the .257 with heavy bullets, but there is less boost with lighter 75-grainers, and that is a fine coyote cartridge for the old Bob.

If you’re looking over a prairie dog town, you would likely still prefer a heavy-barreled varmint rifle in .22-250 for a number of reasons. Even the mild recoil of a .22-250 is noticeable after 50 or so rounds, and barrel weight reduces recoil. Shooting can get pretty busy with prairie dogs, and heavy barrels warm more slowly and cool more quickly than skinny ones. And, yes, heavy rifles are a bit steadier.

But here in the East, I haven’t heated up a varmint rifle in years, nor have I developed a sore shoulder from too many shots with a too-light rifle. My little .243 Savage, which weighs a trim 5-1/2 pounds, is short, light, fast and accurate—just right when roaming the woods for deer or when running coyotes with the hounds.

Every hunter who picks up my Ultralight Arms rifle comments on the 4-3/4 pounds total weight, or at least raises a questioning eyebrow. This might be an ideal deer and predator rifle in, say, .243 Improved, or in plain .243 for hunters who do not handload.

Mel Forbes makes these rifles to benchrest standards, and presently, they are quite expensive.

But he has just started a business called Forbes Rifles. He will continue to make the lightweight stocks while an outfit in Maine makes the barreled actions and does the assembling to Mel’s specifications. The complete assembled rifle is expected to retail at right around $1,200.

Not cheap, but when you compare it to the price of a quality big-game rifle and a separate predator rifle, well, you can do the math.